When we talk about sound in film, we often focus on how it feels. We talk about sound as being immersive, emotional…perhaps even cinematic. But just as important is where that sound lives. Is it something that your characters can hear? Or is it there only for the audience? That’s the key distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound. One exists within the world of the film. The other floats above it, unseen but very much felt by viewers.

Understanding that difference as a filmmaker helps shape the rhythm of a scene, affecting tone, pacing and the emotional impact. Whether you’re editing a moody drama, a documentary, or a fast-cut commercial, knowing when to keep sound grounded, and when to let it drift into something more symbolic, is what separates the “good enough” edit from the great one.

What is diegetic sound?

Diegetic sound is any audio that exists inside the world of the film. If a character can hear it, it’s diegetic. That includes things like:

- Dialogue between characters

- Footsteps on the pavement

- A record playing in the background

- Car horns, weather, doors creaking, anything captured (or meant to be perceived) in the scene itself

Some diegetic sound examples:

- In Children of Men (2006), the sound of explosions, glass breaking and soldiers shouting during the long takes is captured as part of the scene. The characters hear it exactly as we do, which heightens the realism and chaos.

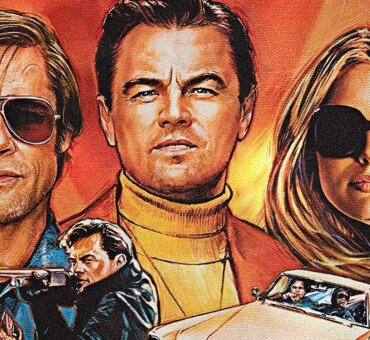

- Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2018) is full of diegetic sounds. A radio plays in the background as Brad Pitt’s character Cliff drives through the streets of Los Angeles. The music here is diegetic as it’s coming from the car stereo. It’s the perfect way to set the mood, era, and tone. That’s the beauty of diegetic sound: it does narrative work and world-building.

Music tends to be one of the most common diegetic sounds if it’s coming from an on-screen source, like a character walking down the street with headphones on. Think about a jukebox in a bar, a band at a wedding or someone playing guitar on a porch. The characters hear it, and it’s part of their environment.

Diegetic sound is often your base layer. In other words, it represents the sounds that anchor your story in a believable space. But it’s also what you layer around it, and how that works in tandem with the diegetic sound, that gives your storytelling more depth. That’s where non-diegetic sound comes in.

What is non-diegetic sound?

Non-diegetic sound is any audio that doesn’t exist in the world of the film. In other words, the characters don’t hear it, but we as the audience do. This can include things such as:

- Narration or voiceover work

- A musical score or soundtrack

- Stylized sound design (like an ominous swell before a reveal, or a tonal boom to punctuate a cut)

These elements live outside the frame. They’re not there to describe the literal world but instead, they shape how we feel about it.

Some non-diegetic sound examples:

- The rising, ticking score during the beach landing in Dunkirk (2017) isn’t part of the environment, but it makes your chest tighten. This is a classic Christopher Nolan – Hans Zimmer collaboration, designed to keep ratcheting up the tension.

- The voiceover in The Shawshank Redemption (1994) can’t be heard by characters. It’s just for us, binding the story together like glue, giving it real warmth, perspective, and emotional gravity. Without it, the film would feel far colder and more distant.

When used well, non-diegetic sound becomes an invisible narrator, hinting at a character’s inner state, building tension long before anything happens, or giving the audience emotional information the characters don’t yet know.

Diegetic vs. non-diegetic sound

So why does it matter? Why should you, as a filmmaker or editor, care whether a sound lives inside the story or outside of it? Simply put, it’s because that choice shapes how your audience feels and reacts to the story. Diegetic and non-diegetic sounds help you hone in on the emotional tone of a scene, as well as give you more control, and further clarity for your audience.

Emotional tone

As we’ve established, diegetic sound helps in keeping things grounded. It feels very real. When you use only what the characters hear, you let the audience sit in the scene with them, as if they were part of the moment.

But the second you add a non-diegetic sound, you begin to shift that perspective. With non-diegetic sounds, you’re guiding the viewer’s emotions more directly. This can make a scene feel more stylized, poetic, or even surreal, which are all powerful tools when used with vision and purpose.

Take Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010). Han’s Zimmer’s infamous ticking, slowed-down “Time” theme during the dream collapse isn’t something the characters hear as it’s purely for us, the audience. It increases the tension and stress levels, reminding us that something far bigger is happening beneath the surface, emotionally and structurally. It draws you in, leaving you on the edge of your seat.

Clarity

Both diegetic and non-diegetic sounds give the audience cues about what’s happening, how to feel about it, and whose perspective we’re in.

A voiceover in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) walks us through Henry Hill’s rise and fall, giving context that the visuals alone simply couldn’t cover. It’s non-diegetic, adding an essential layer of clarity that binds the narrative together across multiple time jumps and shifting tones.

Ray Liotta’s voiceover takes us deep inside Henry Hill’s head, not just telling us what happened, but more importantly helping us understand how he saw the world. It anchors us across the time jumps and tone shifts, while also giving us essential insight into his moral ambiguity. Without that iconic voiceover, the film might feel quite disjointed or emotionally flat.

Creative transitions

Nowhere is the line between diegetic and non-diegetic more artfully blurred than in the opening of Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver (2017), where the music dictates the transitions and cuts of the scene. The first car chase kicks off with Baby pressing play on his iPod. That’s a diegetic sound. The music is playing through his headphones, so only he can hear it in the world of the film. But as the audience, we’re privy to this, too.

Then, as the chase unfolds, that music takes over the entire sequence. Gunshots, spike traps being laid, tire screeches and brake slams are all cut furiously to the beat. It’s rhythmic, mesmerisingly choreographed, and feels almost like a music video rather than a traditional action scene. The sound blends between both diegetic and non-diegetic, and the result is one of the most immersive, propulsive intros in recent memory.

Blending diegetic and non-diegetic sound

Once you understand the difference between diegetic and non-diegetic sound, you can start breaking the rules on purpose, and that’s where things can get interesting.

Some of the most emotionally layered or stylistically bold scenes in film happen when sound crosses these boundaries. When music or effects drift between in-world and editorial, you’re designing and playing with the audience’s perspective, shaping how they feel, even if they can’t quite explain why.

It’s like we discussed above with Baby Driver (2017). Sometimes Baby’s listening to a song in his earbuds (diegetic), but the edit pulls that same track into the full mix, syncing it with the intense action (non-diegetic). While on one level yes, this gives the scene real energy, more importantly, it tells us something about Baby. He’s someone who filters the world through rhythm. The music is how he copes and stays focused. So Edgar Wright’s audio choices are about delivering key information on this character.

In Stranger Things, synth music often starts as non-diegetic mood-setting, but later echoes through scenes in-world, bleeding into radios or tape decks. It creates a blurred reality where the show’s nostalgic soundscape becomes part of the environment. Did someone mention running up a hill?

One film where the blending of diegetic and non-diegetic sounds is essential is Uncut Gems (2019), where the audience experiences a very curated chaos through the sound design. There are layers and layers of dialogue built into every sequence, all blended into each other and set against the rising score, expertly designed to create increasing discomfort and anxiety. It’s intentionally using too much diegetic sound in order to unnerve you. Some comments on YouTube summarize it perfectly:

“I noticed almost everyone in the film is shouting. It’s like trying to listen to a conversation in a huge crowd, it really builds up the anxiety for me.”

“What I love about Uncut Gems is simply that it actually makes you feel something. Doesn’t feel like just a movie, but you feel like you’re part of the world, it’s like zoning out to beautiful music.”

These moments work because the filmmakers understand the rules and know exactly when to bend them. If you’re working in post and want to experiment with this kind of rule blending, Musicbed’s cinematic SFX and music give you the palette. Whether you want that slow bleed from ambient sound into score, or you’re syncing an emotional moment to a rhythmic transition, having clean, emotionally tuned assets makes the whole process far easier.

Matching the right sound to the right world

The best sound design choices are aiding and guiding the story. Whether you’re building a gritty street-level doc or something more dreamy and stylized, your sound palette should reflect that world. That’s where having access to curated SFX like Musicbed’s really pays off.

Here’s how to think about matching the right effect to the right context:

For human stories (like indie dramas or documentaries)

For this type of work, you want to focus on Foley-style realism. Look for textures like fabric shifts, footsteps on different surfaces and small mechanical sounds. These elements help sell the authenticity of a scene without drawing attention to themselves.

Let’s take a quiet evening scene set inside a house as an example. If our interviewee for the documentary is recounting a story from that evening, then layering in subtle chair creaks, footsteps on hardwood, and the faint click of a light switch can help make the house feel lived in, while grounding your audience there in the middle of that story.

For stylized edits or rhythmic pieces (music videos, short-form brand films)

For this type of edit, you want to think percussively. You should search for whooshes, tonal transitions, risers and stylized hits that can help to drive pace and emotion.

Let’s say you have a product launch video. You might try something like syncing quick cuts to tonal pings and rhythmic slams.

For high-impact action or genre work (thrillers, sci-fi, horror)

In this cinematic world, you’ll want heavier, more designed effects. Think about metallic scrapes, bass-heavy impacts and eerie drones. These are your tension builders.

Let’s take a short horror scene where our protagonist is hiding in a kitchen cupboard as the serial killer stalks the house room by room. To create real tension and unbearable anticipation, you might build a moment from a subtle ambient hum, layering in creaking metal and hushed breathing over a rising score, all before a jump cut with a loud boom as the cupboard door flies open.

How can Musicbed help?

Our SFX collection is organized to make this part of the edit much easier. You don’t have to waste hours digging through a massive mess of random sounds. Instead, you’re choosing from a toolkit that’s built around emotional storytelling. Each sound is crafted with cinematic context in mind, so you can focus on shaping the moment instead of endlessly EQing a dodgy download.

Whether you’re crafting realism, rhythm, or full-blown chaos, it’s about picking the sounds that match your world. The clearer your intention, the more impact each layer is going to have.

Wrapping up

The more you understand the role of diegetic and non-diegetic sound, the more control you have over how your story feels. It’s all about shaping emotion, guiding attention and building a world that your audience can truly feel.

And don’t ever let the rules box you in. Once you’ve got clarity on what your characters hear versus what your audience hears, there’s a lot of room to play. Take after other directors and bend the lines and perspectives, creating audio transitions that feel bold, intentional and cinematic.

This is where a trusted resource like Musicbed becomes more than just a convenience. It’s your creative partner. Whether you’re laying in realism with tactile Foley-style sounds or syncing a story beat to a rhythmic hit, the quality’s all there, ready to be used in your timeline right now.

So go ahead and start experimenting, layering and reframing. Great sound design is about purpose and vision. The right sound in the right moment says a lot more than any line of dialogue ever could.