When you think about all the trials and tribulations that go into making a film career, finding a mentor to learn from just makes sense. That’s where David F. Sandberg comes in. He’s made it. His name is behind massive hits like Lights Out, Shazam!, Annabelle: Creation, and the upcoming Shazam: Fury of the Gods. But, he’s also been completely candid about what it took for him to get there. Through his YouTube Channel, he’s uploaded incredibly personal, honest, and flat-out entertaining video essays about the art of filmmaking and the art of being a filmmaker—two completely different things.

So, after poring over his content, we decided to outline a few key takeaways—some observations from his videos and some observations from a broader perspective. We’ll include links to the videos throughout, so use this article as a springboard into the rest of his content. As you’re about to see, it’s a gold mine for filmmakers at every level.

Movies Are Problems—Creativity Is Problem Solving

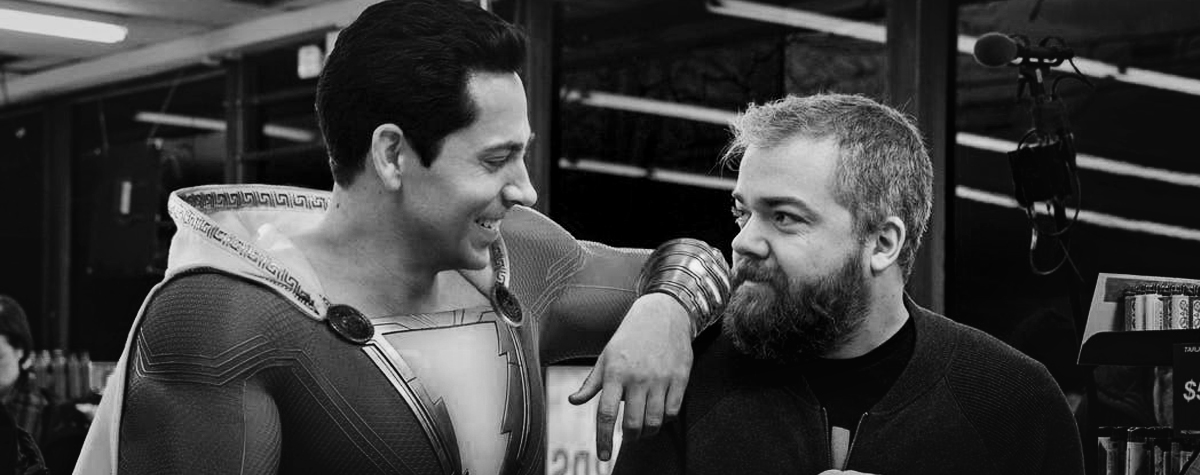

One of David’s most illuminating videos focuses on the idea of problem-solving, primarily in his feature film Shazam!. In it, he offers some great insight into how he approached problems during production, but it also hints at a great truth: films are problems. “Every scene will have problems to solve, no matter how simple the scene,” he says at one point.

And it’s true. Sometimes, the idea of creating a film is romantic. Your vision unfolds before your eyes. We latch onto the inspirational moments but completely forget to consider the fact that every brilliant idea produces countless little problems that either need to be solved or circumvented.

For example, David explains the fact that several of his characters in Shazam! run outside with jackets on, do nothing, and then run back inside, which creates all sorts of continuity problems. Eventually, as you’ll learn in the video, he did find solutions and those solutions eventually led to something that was actually better than the original scripted version:

You’re going to have some sort of problem to solve in every scene, but that’s kind of the fun of it. And, when you come up with a solution that actually makes things better, it’s awesome. But, working with movies has kind of ruined video essays and film analysis for me because you just never know if something was part of a brilliant plan or it just happened to turn out that way because a problem had to be solved on the day.

And that brings up a great point. Sometimes the genius of a film may have never been intentional at all. Maybe it was just a talented filmmaker scrambling to find a solution to a problem and stumbling upon something greater. Maybe the genius is the fact that the film got made at all. In the end, it’s helpful to recognize that films are problems and there’s no such thing as creativity without problems. So, when they arise, just thank the film gods and get to work.

Your Vision Is Secondary to the Viewer’s Experience

An overarching theme of David’s filmmaking advice is perspective. Whether he’s thinking about the sound of a film or even the role of darkness in horror movies, he’s continually talking about how an audience is receiving the product more than what he’s trying to say with that product.

You may think making a movie is personal, but it’s not. In fact, the whole reason you’re making that movie is that you want people to watch, experience, and (most importantly) enjoy what you’re making. So, it makes sense to consider your audience when you’re making decisions.

Take, for example, David’s exploration of sound. In this clip, he compares the viewing experience of a clip with poor sound quality and good imagery and bad imagery with good sound quality:

Recording good sound is perhaps not as sexy as capturing really good-looking images, but it is just as important if not more important.

And that’s the key. How “sexy” or enjoyable a process is for you is irrelevant to your audience if it doesn’t serve the greater goal—entertaining your audience. You may need to sacrifice something you hold dear (here’s looking at your one-takes and long-takes) to keep the pace up and keep the audience engaged.

And then, there’s the lesson of listening to your audience. When he was conducting test screenings for Lights Out, David learned a hard lesson about endings:

It felt like they were loving this movie. It was great. Then, I saw the test scores, and it was clear that they didn’t quite love the movie. It turns out they didn’t like the ending. We sort of overstayed our welcome and tried to do a little too much stuff. We had another test screening, showed the audience the exact same movie, but we just ended it five minutes earlier. We just cut it right there. And now the test scores went through the roof. They loved it. A bad ending can undo almost everything you did before it.

Again, even if you loved those last five minutes it doesn’t really matter if the audience didn’t also love those last five minutes. As Faulkner said, you have to “kill your darlings” sometimes. But, once you’re able to take that step, you’re well on your way to making a film people want to watch.

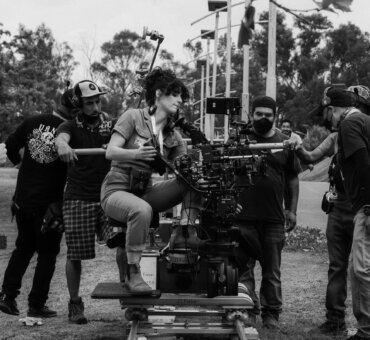

Energy on Set Matters

The process of making a film will ultimately inform the film. Something David explores in this wisdom-packed video speaks to a key role for the director. It’s not just about putting a film together, it’s also about defining the energy of the set—which will impact the final product in ways you may not see yet.

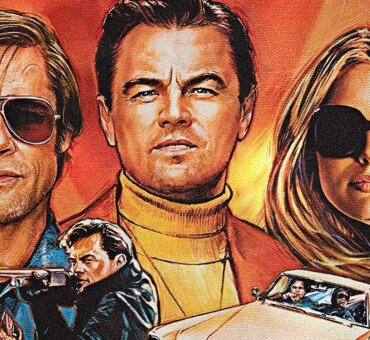

Copyright: © 2018 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

His first point is urgency. Many filmmakers, as he points out, come from short films where things move quickly, and shots unfold in sequence. But, on larger features, that’s not how it happens. As the director, you have to be intentional about what a scene requires from actors and how it will impact the following scenes, or you may find that an energetic take one day leads to a tepid take on the next. It’s about urgency, and that may be something you have to create:

It seems very obvious to really think about where you’re coming from and where you’re going and to discuss that with your actors, but it’s something I see being missed sometimes.

And then, there’s a bit more of a tangible problem. There’s a reason so many actors and directors love live theater—there’s an excitement and energy that can be difficult to replicate in other media, and that includes a camera:

They say the camera adds ten pounds to people, but I think it takes away some of the awesomeness, sort of dulls things down a little bit. Sometimes we have to kind of exaggerate things, make them bigger to reach what you’re going for. You have to kind of aim beyond your target to actually land at your target.

When in doubt, go bigger. David points out that it’s rare to wish a scene or a setting or a camera movement was more subtle in the cutting room. Generally, directors want the opposite. So, be sure you’re getting the coverage you need and the energy you want when you’re shooting. This can apply to shots, performances, practical effects, or, as David points out, even the set design. Ultimately, no one is going to bring the energy a film requires if you’re not also bringing the energy. You have to be the source for the rest of the cast and crew.

Know Who You Are

As we’ve mentioned a few times, David doesn’t hold back in his videos. And, that’s the best part. He’s extremely candid about some of the more sensitive sides of his career and his filmmaking process, which is something that we don’t talk about nearly enough. For example, depression is something he deals with through the process of making a film, and it’s something he thinks many filmmakers will deal with as well:

Not only does it feel like you will never get out of depression; it even somehow tricks you into thinking that everything that came before was shit as well. But, it wasn’t. I’ve been through it so many times now, and it’s so regular, that I know it will pass.

The point is, you have to know about it to anticipate it, and you have to anticipate it in order to defeat it. He knows that he’ll get depressed when he sees the first cut, or even when the film is finished, and he’s learned over time to be ready for those moments. He can know that his brain is saying one thing, but the reality is saying something else.

As creatives, we can’t change who we are, but knowing who we are is even better. In one video entirely focused on being an introvert, David shares the fact that he’s been diagnosed with atypical autism, which doesn’t change anything about who he is, but it definitely changes how he approaches his life and career.

I don’t really care what the label is; I just need to know how my brain works so I can try to improve problem areas or work around them. I have improved tremendously.

Unlike some other crafts and careers, it’s difficult to separate your personal well-being from the film’s well-being. As we said previously, directors must be able to bring everything they have to a project in order for it to succeed. So, if you’re going to make successful films, it helps to have your mental health squared away. It’s a process that takes a lifetime.

In the same video, David brings up the fact that he hates to pitch his work. It’s uncomfortable, and he needs to be incredibly prepared before he can make a presentation. And, he admits it’ll probably never be comfortable, but he knows that about himself, which is everything:

There are directors who are good in the room. I’m not going to mention names, but there’s this one guy who’s done some big movies that haven’t been great and haven’t always done well at the box office, either. But, he’s been hired over and over again because he’s good in a room. He can get you all fired up about an idea and make you go, ‘Yes! Here’s money. Go make it.’ I don’t think I’ll ever be that person. It’s just not who I am. But, there’s always room for improvement. How do you improve at something? By doing it over and over and over. That’s how I learned how to make movies.

If you haven’t stopped in the middle of this article to watch all of David’s videos—first, thank you, and second, you should probably go do that now. They’re poignant, informative, inspirational, and entertaining—and they’re a great look at the realities of filmmaking.

Feature Image Credit: Steve WilkieCopyright: © 2018 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.