While the performances of actors on screen, the lighting and the music all play their vital roles, sound is a crucial element that’s often overlooked. Small details like the sound of a boot sinking into wet mud, or the quick inhale just before a punch lands may be trivial. You don’t notice these things at first. But if you took them away from the scene, it’d make a huge difference. Such sounds are built, performed and expertly layered in by the editors. This is Foley.

Named after Jack Foley, a Universal Studios artist who started adding synchronized sound effects to silent films in the 1920s, Foley has become one of the most important (yet invisible) tools in the filmmaker’s kit. Without it, even the most expensive scene can feel flat.

In this article we will talk about why Foley matters, how it works, and how you can achieve the same sense of realism in your own work (even without a studio full of props and a soundstage).

What is Foley sound?

What exactly is Foley, then? Foley is the art of recreating everyday sounds to match what’s happening on screen. It can be things like footsteps, fabric swishes, the clinking of glasses, or a hand brushing over a table. Foley focuses on the small, unnoticeable details that help breathe life into a scene.

Foley’s uniqueness is in its performance. The sounds are recorded in real-time, synced to a picture, often using improvised propsDuring his work on films like Show Boat (1929), Jack Foley created techniques for syncing footsteps and movement with on-screen action that were executed in one take, straight to tape. There was no editing and no overdubs!

Some classic examples of Foley sound in action

Foley is in every piece of cinema since sound was first introduced, so examples and case studies are endless. Here are a few favorites to look out for next time you’re watching:

A Quiet Place (2018) stands as a true masterclass in Foley sound design. In a film whose entire premise hinges on remaining silent, every minute sound and sonic detail becomes magnified. If you’ve ever wondered “what exactly does a Foley artist do?”, watch this behind-the-scenes video below. Here, the Foley artist meticulously crafted the film’s soundscape, escalating tension to nearly unbearable heights.

In Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), the emphatic punches were actually made with a baseball bat hitting a pile of leather jackets. Listen out for each of them in this clip. It’s almost a little slapstick, but it really works and has become somewhat synonymous with the Indiana Jones franchise.

In Saving Private Ryan (1998), the gritty textures of gear, gravel and boots were built almost entirely in post through Foley artistry. The sniper scene is a particularly fine example of Foley at work. All of the little details make this feel very real, grounding the audience in the scene and consequently making us feel much more tense. You can feel yourself almost holding your own breath as we try to stay as still as possible, evading the sniper’s gaze.

While much of Star Wars is sound design (could link to the first article here), Foley was essential too. The subtle fabric movements of Jedi robes, holster grabs, footsteps in the various locations — all of these were performed in sync by artists like Ben Burtt’s team to help ground the fantasy in something tactile and real. The infamous end duel from The Empire Strikes Back (1980) is a really great case study for Foley.

The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) trilogy is also rich in Foley sound design. Every footstep on snow, chainmail clink, and jingle of a horse bridle was rebuilt with custom props and surfaces. The scene where the Rohirrim are marshalling at Dunharrow in The Return of the King (2003) brings all of this together. Imagine how much work and effort it takes to create Foley for scenes like this!

Foley sound effects vs. digital sound effects

Foley and digital sound effects can serve the same purpose. Essentially, they’re reinforcing what we see on screen, but the way they’re made and the way they feel are quite different.

First and foremost, Foley is performed. It’s tactile. Someone physically puts on gloves, walks across gravel and rustles the fabric, all timed to the movement in your scene. This is sound design that’s built by expert ear and intuition. It can be improvised at times, too. As Foley is recorded in real-time and synced to picture, you’re literally acting the sound.

On the other hand, digital sound effects (SFX) are pre-recorded audio clips. They might come from a sound library or be created synthetically using software. They’re dropped onto the timeline, trimmed, faded and layered. Digital SFX can be incredibly effective, especially for big-impact moments or abstract elements such as sci-fi weapons.

Another thing to note is that, somehow, Foley feels more “real”. It’s because it carries the imperfections of physical motion. When that shoe scuffs slightly on the third step, we hear some variability that feels normal and real to an audience.

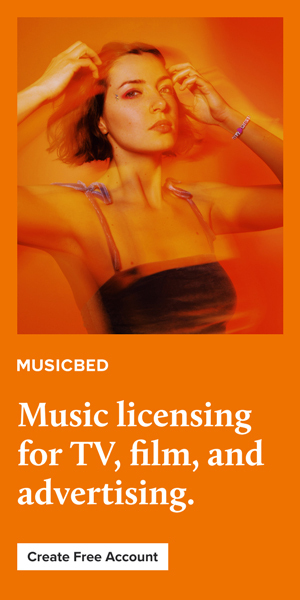

Foley and digital SFX are not mutually exclusive. Most modern sound design should and always does blend the two. For example, you might use a layered whoosh from Musicbed’s sound effect collection for a certain gesture, then add in a touch of Foley like a coat rustle, or the creak of some old leather gloves.

Intent is the key here. Use Foley when you want to feel someone’s physical presence, and use digital SFX when you need to stretch reality or punctuate a moment. Sometimes, if budgets are tight and you need to move quickly in post, using digital is the only way. If you don’t have the time or means to set up and perform Foley for your film, then that’s where a pro SFX collection or library can really step in to elevate your film, giving you the realism of Foley, with the flexibility of digital.

Creating foley at home vs. using cinematic libraries

If you’ve ever tried recording your own Foley, you know how fun (and frustrating) it can be. Just scroll back up to that behind-the-scenes watch on A Quiet Place to remind yourself of how much work goes into great Foley.

At home, you’ll start with good intentions. A pile of props and a quiet room, maybe a towel on the floor for some footsteps. But then you start to notice the fridge humming in the background and you can’t get it to stop. Then your mic clips at the wrong moment, and you realize your jacket rustle doesn’t match the rhythm of the actor on screen. Foley is part performance, part precision and part patience. When it works, it is undoubtedly quite magic. But when it doesn’t, it eats into your entire post schedule (and perhaps your sanity, too)

The pros of DIY Foley are that it gives you full control, and can be really satisfying from a creative point of view. But the drawbacks are that it’s time-consuming and it’s especially tricky to nail that big-screen polish without a proper, treated space and professional high-end gear. For a lot of filmmakers, especially in the indie or micro-budget world, this tradeoff isn’t very sustainable, unfortunately.

So that’s where you get help from specialized sites like Musicbed. Our curated sound effect collection can offer cinematic sounds that are designed to feel like Foley. The recordings are textured and physical, and they’re performed with nuance and variation. When it comes to the edit, you’re choosing from layers that sound lived-in and are expertly tuned.

How to use Foley sound in post-production

You don’t need a mixing stage or a ten-year audio background to start layering Foley. All you need is a good ear, a bit of patience and the right workflow. Whether you’re recording Foley yourself or working with prebuilt sounds, the goal is essentially the same: physicality. You want your scene to feel like it’s actually happening. If the sound disappears right into the performance, so that you don’t notice it, then you know you’re doing it right.

Start with the performance

Watch the scene and note the physical actions that need a sound: footsteps, clothing shifts, hands grabbing objects, etc. It’s important to remember not to overdo it. It’s all about grounding the action in a sense of realism.

Layer intentionally

In most NLEs (Premiere Pro, DaVinci Resolve, Final Cut), you can stack audio tracks and tweak levels quite quickly. So start with the core sound (let’s say a bootstep) and then add subtle textures like gravel crunch or a pant leg brushing. Again, remember that you want to keep it quite simple. Two to three layers is usually enough as a rule of thumb.

Use EQ to help it sit in the mix

Raw Foley can sound a little too close or too clean, and it’s an indicator of amateur work. Consider using a high-pass filter to cut low-end rumble, or roll off the highs to match the scene’s tone. If the character is outside, give the sound some reverb or slapback delay to make it feel like it’s bouncing in space. These little details matter, and can help raise your film to the next level.

Timing is everything

The reality of sound design is that you’ll need to experiment and rewatch each scene multiple times to get it right. Don’t be afraid to pull sounds a few frames earlier if they feel sluggish, or delay them slightly for dramatic tension. Remember to trust your gut (or your ear, in this case). If something feels off, then nudge it. Even a few milliseconds can make the difference.

Don’t oversaturate

As we’ve been hammering in this section, oversaturation is where a lot of beginner mixes fall flat. There is such a thing as too much Foley. If everything has a sound, then absolutely none of it can stand out. So let moments breathe. Sometimes, the absence of sound draws attention better than another layer.

Wrapping up

Foley is one of those things you don’t notice until it’s missing. It’s what makes a scene feel very real, even when nothing about it was actually recorded live. Every footstep and hand-on-glass moment builds a bridge between your audience and your characters, turning your moving images into something tangible. It’s worth putting in as much effort into your sound design as you did into your visuals. And the great thing is, you don’t necessarily need a professional Foley stage to get there.

With sound effects like Musicbed’s cinematic SFX collection, you can bring that same realism and texture into your work without the hours of mic setup or trial-and-error. These sounds are crafted with the same care and nuance as true Foley, ready to drop into your timeline and feel like they’ve always belonged.

If you want your edit to sound as good as it looks, don’t overlook these small details. Layer with intention, and let the world you’ve built be heard (and felt) properly, one footstep (or Indiana Jones punch) at a time.