Win, lose, or draw, there’s something respectable about diving headfirst into something — going for it. The great Annie Dillard puts it nicely: “You’ve got to jump off cliffs all the time and build your wings on the way down.” It’s the tension between gravity and impact that forces us to get creative, build processes, and maybe even escape disaster. Because, let’s face it, there’s nothing quite as motivational as imminent failure.

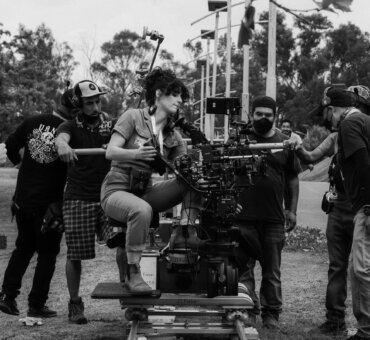

Musicbed composer and overall brave soul AJ Hochhalter experienced this firsthand when he decided to produce his first documentary. And no, this wasn’t an obscure four-minute short. He and director David Altrogge (of production company Vinegar Hill) undertook a feature-length examination of the bourbon industry. Luckily, the resulting project is a prime example of succeeding before impact. Neat is a beautiful lesson in craft, love, relationships, and time — all from the perspective of Kentucky’s most drinkable export.

We had the opportunity to talk to AJ and David about handling a feature-length production and what makes a great documentary. Cheers.

So where does Neat fit for you? Does calling it a passion project sell it short?

David Altrogge: It’s definitely a passion project for us. I mean, what’s better than making a feature-length documentary about bourbon? But Neat is the third feature we’ve produced since 2007, and this is the first one we went into with a solid business plan. The other two were purely passion projects, and were almost more like film school. AJ, as a producer, brought a business plan and really pushed us to make a film that could reach as broad an audience as possible.

Did it start from a shared love of Bourbon?

David: When I started this film, I wasn’t into bourbon at all. But AJ and I were drinking bourbon down in Lexington, and one of us said, jokingly, that we should make a documentary about it. We laughed it off, but a month later AJ called me and said that he’d been making some phone calls for interviews and getting some traction. I guess that’s how the film was born.

AJ Hochhalter: I’m from Kentucky, so you just have to be into bourbon by default. That’s where I started with this project.

Are you normally this involved in films?

AJ: No. This would be the first time. I’m a composer.

David: Just to be abundantly clear, AJ has never produced a film before this one. [Laughs]

How’d you adjust to the new role?

AJ: I think being a producer just made sense for the region that I was in, and the relationships I already had in Kentucky. The relational side was tough, though. David’s always been my director as a composer and I’ve always navigated the relationship that way. I’m used to getting direction from producers and directors, not being the person in the driver’s seat. It was a little awkward at first. Getting the interest and funding was relatively easy, but there’s so much more to being a producer, especially as it moves towards post production and, in my case, you start to become the composer too.

I’m used to being a slave to the film and the director. You have your skillset, but at the end of the day you do what the film dictates and what the director says, whether you like it or not. It can be hard to re-learn that for each project, but it’s something I always try to lean on. For me as a producer, this was a weird place I’ve never been.

What did you do to get yourself into place?

AJ: I called people. Jennifer Brown is an amazing producer who’s been working with Vinegar Hill for a while. She jumped in and did a lot of the day-to-day logistics — that’s where I felt like I was going to completely drop it [laughs]. Just calling people that I trusted, that I’ve worked with in the past, was huge for me. I didn’t just figure it out. I had people help me figure it out.

Where do you start with such a huge subject?

David: We already knew that distilleries and master distillers were going to be a great place to start, because they’re eager to share the story of bourbon and they’re eager to share their involvement in the story. When we started talking to people, they would start asking us questions. That was the cool thing. Did you talk to this distillery? Did you talk to this guy? We found Freddie Johnson, who’s basically the main character in the film, completely by chance.

AJ: That was during snowpocalypse.

David: Myself and our cinematographer Mike Hartnett were driving down to Kentucky, and we got hit by this massive snow storm that shut down Lexington, Louisville, and the whole bourbon region for a week. All of our interviews were cancelled. The people at Buffalo Trace called us to say that their master distiller couldn’t make it, but said, “We have this tour guide and he’ll talk to you guys.” So we thought, at least we’ll get something on film. But as we were interviewing him, we realized we stumbled upon this incredible story, and that came from just saying “yes” to an interview. Another example of that is Marianne Barnes, who we found out is the first female master distiller since prohibition.

So how do you turn great interviews into a story?

David: That was pretty terrifying. Once we actually got started on the film, and it became more real, it expanded into this infinitely large subject that we had to cover and figure out what story we were telling. It took about a year and a half to figure it out. I’d come home from filming interviews, and I’d say to my wife, “I don’t know if we have a film. We have funding. We’re moving forward. We’re getting great interviews. But I don’t know what story we’re telling.” To me, the biggest challenge was more of the head game — pushing forward even when we didn’t know where we were heading. It was the most consistently challenging thing, not crumbling with uncertainty and continuing to push forward and continuing to shoot after shoot.

So we had this summit with myself, the cinematographer, AJ, and some other people from Vinegar Hill to get our structure nailed down — these vignettes with interesting characters, the history of bourbon, and the process of making it. Once we had that figured out, that’s when we started making progress on the film.

AJ: Yeah, for sure. If you’re naming your film The Story of Bourbon you really have to distill what the story is.

Pun intended?

AJ: [Laughs] Pun intended. The more we learned — us not being bourbon aficionados — the more we could ask questions and figure out what this thing was going to be about. That’s where these unique characters started to come out, these vignettes that speak to the heart of bourbon in a unique way. It causes something to happen. We can talk about it, but until we give the film a structure the ideas can’t form. We work this way a lot from a composer/director standpoint. Until an idea is there — a rough cut with a temp track or whatever — it’s really hard to know what you like and what you don’t. We were waiting for the structure to be defined before we could really get creative.

David: You can shoot interviews all day long and get really interesting people talking about what bourbon represents, but until you have that structure you don’t have a film. It was really freeing for me to know what we had to do, to have a map for how we’re going to finish this thing. It allowed us to get to the rough cut, which was where we had another creative summit session. We watched the film and talked about what else we needed to shoot and what we were missing. That’s where Steve Zahn’s sections came from, and that wasn’t until after the rough cut was done.

That was really surprising when he popped up.

AJ: Good! That’s what we wanted. Steve’s a mutual friend and fellow bourbon lover, and we were really lucky to get him involved. He’s a farmer in Kentucky, and when he’s not on a big shoot he just sells hay to people. He’s easy going and really fun to work with.

Is it the details like those that make some documentaries work and others flail?

David: I don’t know if we can say, objectively, why some fail and others work. There’s so much that can go wrong in a documentary. We wouldn’t have the documentary we have today if we hadn’t found Freddie and Marianne. But when things don’t work for me is when I cut myself off to other people’s ideas and get married to my own. This whole thing worked because AJ had really strong opinions about the story. He wasn’t just a “yes man” for whatever I wanted to do. There was a lot of really good conflict in the process. I think the ending was a good example, with Freddie talking about his father. There was a lot of debate about whether or not we should end there.

AJ: Yeah, there were rumblings. How could we end a feel-good documentary with a somewhat somber story? It just felt wrong, but everything this guy said was so poignant, so we actually decided to lean into that and include him more — so our audience would really care by the end of the film. There was friction in every part of that conversation, just because we really couldn’t mess it up. But our team handled it so well, that it worked.

David: I wish I was an auteur. I wish I was Martin Scorsese or Stanley Kubrick — someone who can just know what’s right and go with their gut. But I’m not that kind of filmmaker, and most other filmmakers aren’t either. So find a team of people you trust, people who are smarter than you, and build this collaborative environment. It’s only going to make your films better, which is why we got into this thing in the first place.

Neat is now available on iTunes. To rent or buy it, click here. You can also license the soundtrack for your own project and explore AJ’s extensive resumé via his profile.