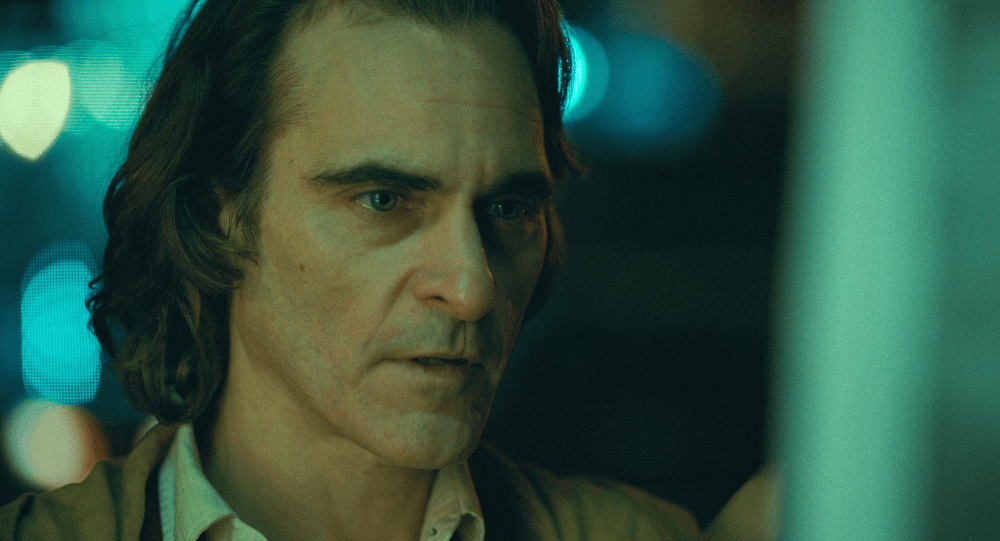

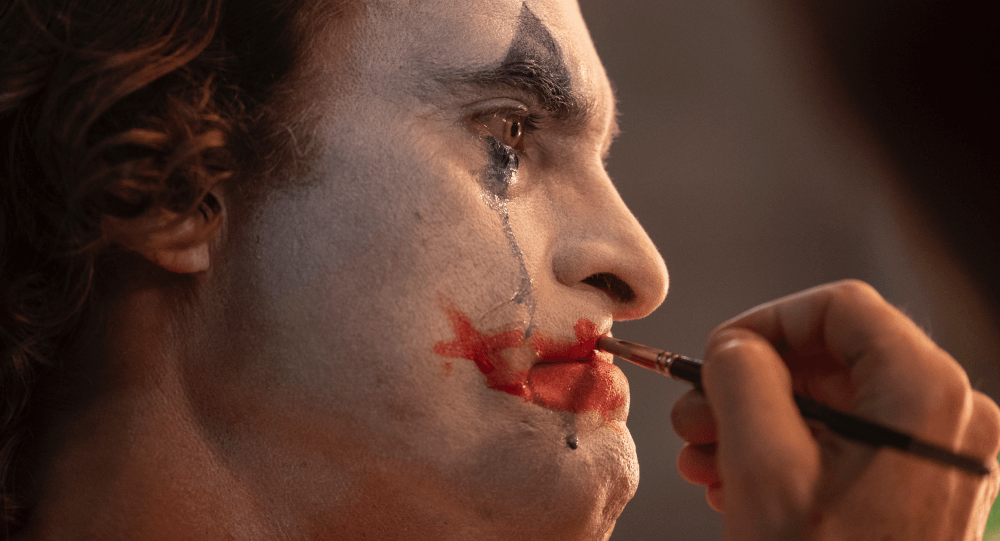

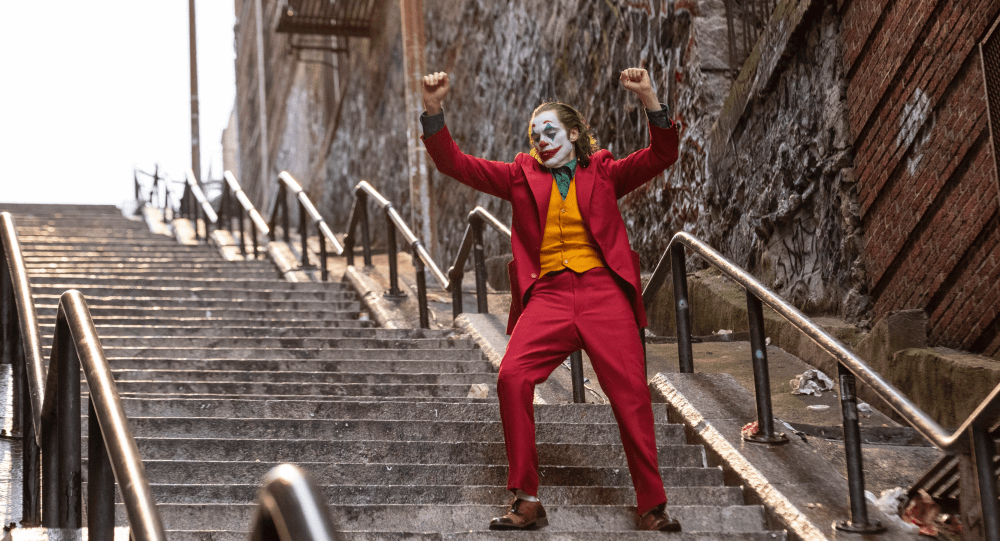

Warner Bros. latest Joker, takes a conscious step away from the stylized trappings of past Gothams, delivering a raw vision of an urban squalor recalling New York from decades past. The protagonist, played by Joaquin Phoenix is a product of these surroundings. The odyssey that transforms him from Arthur Fleck to a clown-faced menace points to how this film is more of a character study than the traditional comic book blockbuster.

On this project, Director Todd Phillips employed many of his past collaborators, including film editor Jeff Groth. He worked on series such as Community and Entourage and later joined Phillips as the editor for The Hangover Part III and War Dogs. The workflow Groth established on these earlier projects required modification to develop the backstory for the DC villain.

Groth’s Non-Traditional Workflow

Joker is a film that is subtle, nuanced, and evocative meaning the edit needed to reflect these qualities to allow Joaquin Phoenix’s performance to progress over time. Groth’s approach to this edit was handled with extreme care to truly reflect the vision of Arthur Fleck’s transformation.

“Previously, I cut scenes as they came in,” Groth says. “But since this is such a character study, we wanted to be able to watch his progression from where he starts the film to where he ends up character-wise. So, I began cutting the scenes in order. For example, on day one, they might shoot scenes 1 and 30 and then shoot scenes 2 and 35 on day two. So I would cut scenes 1 and 2, then leave the rest for later. I was always trying to fill in the early portions to get the movie built. Anytime somebody wanted to see what we had, they were seeing a more refined progression of the edit versus how I would typically cut a film in a more non-linear fashion.”

“Understanding the material is an ongoing process and with a movie called Joker, you know how the story is going to end, so it’s all about how you get there,” Groth says. “But no matter what project you’re doing, the first week or two is always difficult, because a context hasn’t emerged. So, the earliest material usually winds up changing the most by the time you reach the end of the process, when you can make more informed judgments to evaluate what you’ve already done.”

But, one aspect was clear from the very start of the editing process: Joaquin’s performance.

Letting the Performance Lead the Edit

“The first goal of the editing was to stay out of the way,” Groth says. “We didn’t want to distract from the performance Joaquin was delivering. It wasn’t about building something that wasn’t there in the material, because he always delivered the goods—he was phenomenal in his explorations. Once we had a significant amount of the film cut together, we would go back through scenes periodically to see where we could remove edits. Sometimes we wound up letting shots play a bit longer, which let the whole thing breathe.”

”When you get done putting a scene together, it’s very clear nearly all of those bits of purpose have their place,” he explained. “My first cut always runs long anyway, or at least I hope it does. I’d rather try to cut it down than to fill it up, and I’m taking a little extra time during that first assembly to make sure all these aspects are represented.”

This process required removing some extraordinary work from the first cut. Having worked with DP Lawrence Sher before, Groth knew he could rely on plenty of coverage from shooting. But, he also knew Sher shoots with intentionality, so it was important to leave certain angles and frames. They each had a purpose, so Groth was able to lean more heavily on the creative energy captured on-set.

Sher operated B-camera, along with camera operator Geoff Haley, he often explored alternate ways to visualize a scene, sometimes taking the camera across the 180-degree-line. “Joker is not a traditional film or storyline, so traditional film rules were a bit more flexible than normal. Instead of traditional rules and beats, we were able to use the performances as the North Star within the edit.”

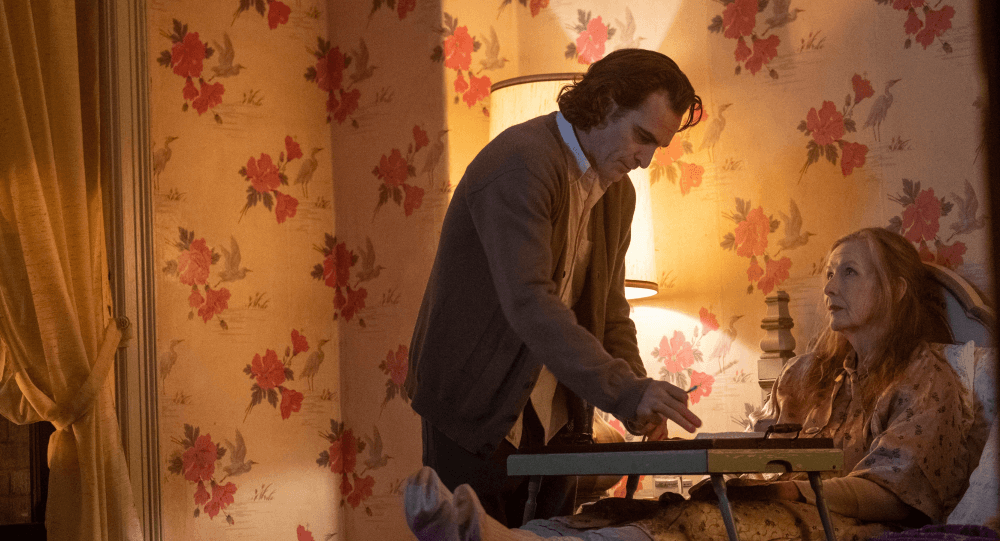

“Having something captivating to look at lets you get away with things. And if the question ever got asked, ‘what should we cut to?’ the answer would be, ‘cut to Joaquin.’ He is in every scene of the movie and very nearly every shot. There are scenes with his mother where the camera is focused on her but he is still present in frame, and there’s always interest; it’s a whole-body performance.”

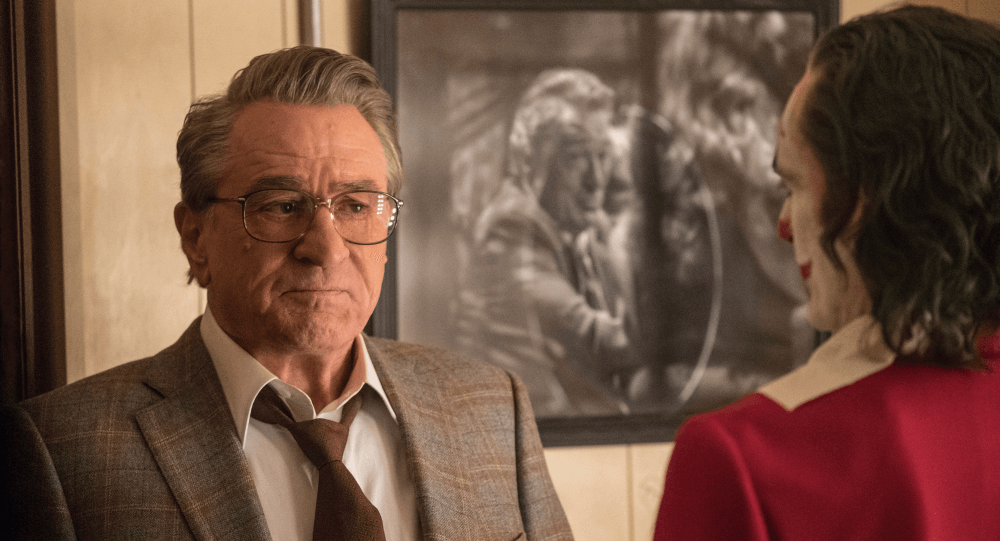

The Murray Franklin Show

Groth said the planning and execution of Arthur’s appearance on “The Murray Franklin Show” in the film needed the most planning, requiring a digital pre-visualization before shooting even began.

“It was a very long sequence featuring a large and elaborate set. Throughout the scene, there are four television cameras running along with the three or four movie cameras,” Groth says. “So we had four live feeds coming from those cameras for every take, plus a view of the live cut being handled upstairs. Video assist was getting stuff from all of these sources.”

Groth and his team built the talk show scene each day, incorporating more from the TV camera imagery, into what he called the master line cut. He used it like a live edit, eventually cutting it into a master version mimicking how an actual viewer would have seen it on a broadcast.

“That version included all of our favorite performances,” he says. “Although it didn’t cut together perfectly—there are some continuity errors—it did cover all the story points and gave us a place to start on the rest of editorial.”

Creating Gotham City

Even though the film’s version of Gotham looks more like a late-70s film, it still required a fair amount of modern visual effects to extend the look beyond traditional art direction. Lead post-houses Scanline VFX and Shade VFX helped to make the city look closer to an older New York than the Gothams from Tim Burton’s films and Christopher Nolan’s films.

In moments where Groth needed more time at the end of a scene, he used the VFX work to extend the shot, giving the audience more of a full-frame visual in the end.

“We all paid attention to making the city feel real, and yet also something not specifically New York,” he explains. “Even the sirens you hear are different. We temped with European sirens just to give it something extra. Then, working with the sound people, we stressed that if they looked closely, they could see it wasn’t quite New York, which inspired them to come up with a sound equivalent that was something a little bit unique.”

Sound & Score

Groth elects to temp-track every project, using it as a guide or inspiration to find a natural rhythm in an edit. He was able to use six tracks that composer Hildur Gudnadottir [Chernobyl, Mary Magdalene] put together before shooting that “perfectly encapsulated” the tone of the film.

But, even in the finished film, Groth said the goal was to keep the music’s function in parallel with the rest of the film. As a nuanced character study, they needed a sound that wasn’t going to “pile on emotion” that wasn’t being added by an existing performance. He said they even removed music during many scenes to keep the focus on Joaquin’s performance.

“Many scenes, built on Joaquin’s performance, were standing on their own, revealing the colors we needed,” he says. “We didn’t want to be heavy-handed with this very unique and distinctive score, which could happen if we played it too often. Hildur was very open during this whole process, and sometimes she was the first to say the score might not be necessary for a particular moment.”

The mood and atmosphere guided everything. The amount of detail even seeped into the titles, which were produced with a pre-digital look through traditional filming and digital composition. The production team’s commitment to authenticity and performance shines through in every aspect of this film, revealing a nuanced portrait of a villain who’s been easy to write off as a cartoon character in the past.

For Groth as an editor, it’s about the basics of story and emotion, the way film can create a truth that’s far more complicated than a generalization.