In the short film Cooking Up a Storm, edited by Lucas Harger, the process of preparing a meal is imagined as an analogue for a storm. It’s a clever concept, but the execution is what puts this project over the top. The cinematography is beautiful, the sound design is spot on, and the editing is a lesson in pacing and concision. There’s much more going on here than initially meets the eye.

We asked Lucas to break down his thought process and work process on Cooking Up a Storm.

BACKGROUND

This was an internal project for the studio I work for, Bruton Stroube. We were looking for a new way to showcase food. A lot of the food work you see is food porn: really tight, close, oversensualized food shots, which are great and serve a market. But we wanted to move toward something more cinematic and lifestyle driven. So Tim Wilson (my director and partner) came up with this concept that used storm sound effects and metaphors. As the editor, I came in on this project early on, when we first started talking about this structure of the calm before the storm, the storm itself, and the calm after the storm — the finished product. We knew the concept and the structure, but we didn’t know how it would all come together until we got into the edit.

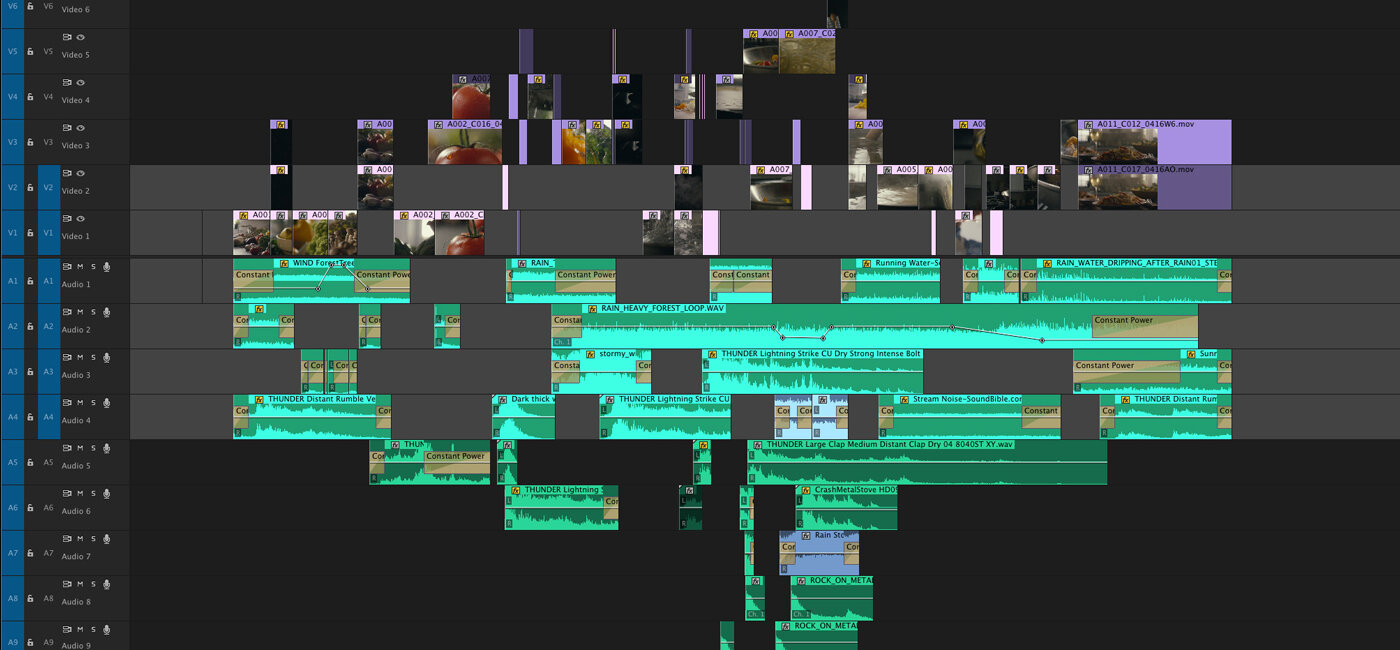

ORGANIZATION

The first thing I did when I got all the footage back was organize it into different stages of the storm. There weren’t any natural sounds captured with this, so I didn’t have to do any syncing or audio prep. I just organized the clips and started laying out all the takes on the timeline and pulling selects within the different storm movements. Some of the shots had action in them. Like the stove turning on. It’s off, then you see the flame, then it’s on. Something changes in the shot. Other shots were more fluid and didn’t have a specific action in them. Nothing changed from beginning to end. So it was a lot of finessing to figure out which scenes should involve action, which scenes should be fluid, and which could represent the different aspects of a storm.

Over the past few years, one of the big things that has changed about the way I edit is how I look at footage at the beginning of a project. I used to immediately go looking for perfect performances and takes. But now I’m much more interested in the fringes of the footage. Moments or shots that maybe weren’t necessarily intended, but they’re still great. Unexpected moments. Because there’s often real gold in there.

SOUND DESIGN

This whole concept was built around sound design. As an editor, that means I need to build specific moments into my timeline that will inform the sound designer what I’m thinking of. I tend to build out my own sound design as much possible. I try to think through everything in my edit so when the sound designer gets it ⎯ even if they go in a totally different direction ⎯ they never question what I was going for. Usually they replace my sound effects entirely with much higher quality sound. They might take the bones of my concept and expand on it. Make it 100 times better. For example, during the stirring noodles scene on this project, I’d originally used the sound of rushing water to represent flooding. But our sound designer took it in a different direction. He put these big, low drones and swells there, which are perfect. That’s exactly what should be there.

PACING

Going in, I knew we wanted to have this calm before the storm and then a calm after the storm. In theory, that would mean longer shots at the beginning and end, and shorter shots during the storm section. It turned out the average shot length at the beginning was 3.25 seconds, then 1.5 seconds in the middle, and then a huge, long ending shot. But it’s important to see that within the storm section, there’s a big variation in shot lengths. The whole thing ebbs and flows. That’s what interesting pieces do ⎯ they achieve their pacing by creating micro-moments within the larger chunks. Interesting content tends to have a lot of pacing changes. If something is blazing fast for too long, it gets boring. If something is too slow, that gets boring. The ebb and flow make a piece interesting to watch. Even in the beginning of the piece, in the slow section, there are a couple of less than two-second shots, which hint that something is coming. You have to look at pacing on that micro and macro level at the same time. How do they advance the story or the emotion of the piece?For me, especially on a piece like this, I tend to cut from intuition. I cut from the gut. I don’t overthink it. I try to get an edit out as fast as I can. And if there’s a cut I’m not feeling, I duplicate my sequence and start a new one. Then I duplicate it again and try a new one. I keep versioning it and seeing what feels best for specific takes. I then go back and collect all of those into a master cut.

SPECIFIC CUTS

Dry Pasta

There’s an insert shot after the pasta is broken that’s key to making this sequence work. They break the pasta, you see the bits falling on the table, then you see the peas hitting the pan. It seems like a simple little three shot. But it’s the insert shot that gets us from the pasta to the pan, which otherwise don’t have anything to do with each other. The pasta hitting the table is an audio transition and an action transition. Now things are falling. Now things are hitting the pan. It feels seamless, but it’s actually a big leap. It works because of those 13 frames.

Final Shot

This is an interesting cut because we start out really tight on the shrimp and sprinkle seasoning on it. Then we cut to the finished plate and sprinkle Parmesan cheese on it. I like this cut a lot because it’s actually a huge jump. We’re going from shrimp in a pan to a completed dish. Tight to wide. A lot is changing. But it works because there’s the consistent action of sprinkling. Without that, it wouldn’t work. At least not as well.

Pan Rotating

I used the camera movement as a transition here. The camera rotates around the pan, then we go to the spoon rotating in the pasta, and then to the salad rotating. The camera movement makes it all feel connected. When we see the spoon again, it’s something we’ve seen before; so we accept it as a part of the story. There are a lot of little bridges like that to get us from one shot to the other without making everything feel disconnected. It would be easy for a piece like this to feel like a lot of random cooking shots. That’s a trap I see a lot of editors fall into. They cut to an action. Cut to another action. Cut, cut, cut. It’s very dry and regimented instead of feeling like there is a reason for the cuts. Like the cuts are taking us somewhere. They feel the need to let an action play out completely. There’s an old editing rule of thumb: Arrive late, leave early. If you consider that rule during the cut, you being to uncover a more engaging and interesting edit.When I first started cutting this piece, I was really into speed ramps. There are definitely a handful of speed ramps still in there, but I was using them to transition between shots, to amp up the chaotic nature of the storm. At the end of the day, I started pulling back a lot of that and went with straight cuts. It felt right for the pacing and rhythm of the piece. I wanted to build the momentum through cuts rather than ramping. That’s a consistent thing with me. I go too far one way on the first cut, and then I pull back all of those things in the final. There are always a million things I’d do differently when I look back on a project. But with filmmaking, it’s so important to ship. Learn from every project and just move on to the next. Put together a body of work that is building upon itself over time, rather than obsessing over one cut for months or years. There’s a time and place for obsession, and there’s a time and place for shipping.