A significant number of editor Andrew Weisblum’s credits reflect sustained collaborations with noted filmmakers, including Darren Aronofsky (The Wrestler, Black Swan—for which he received an Oscar nomination—and Mother!), Zal Batmanglij (The East, The OA), and Wes Anderson. In Anderson’s case, Weisblum’s association dates back to The Darjeeling Limited, and it even includes supervising editor roles on the director’s animated features.

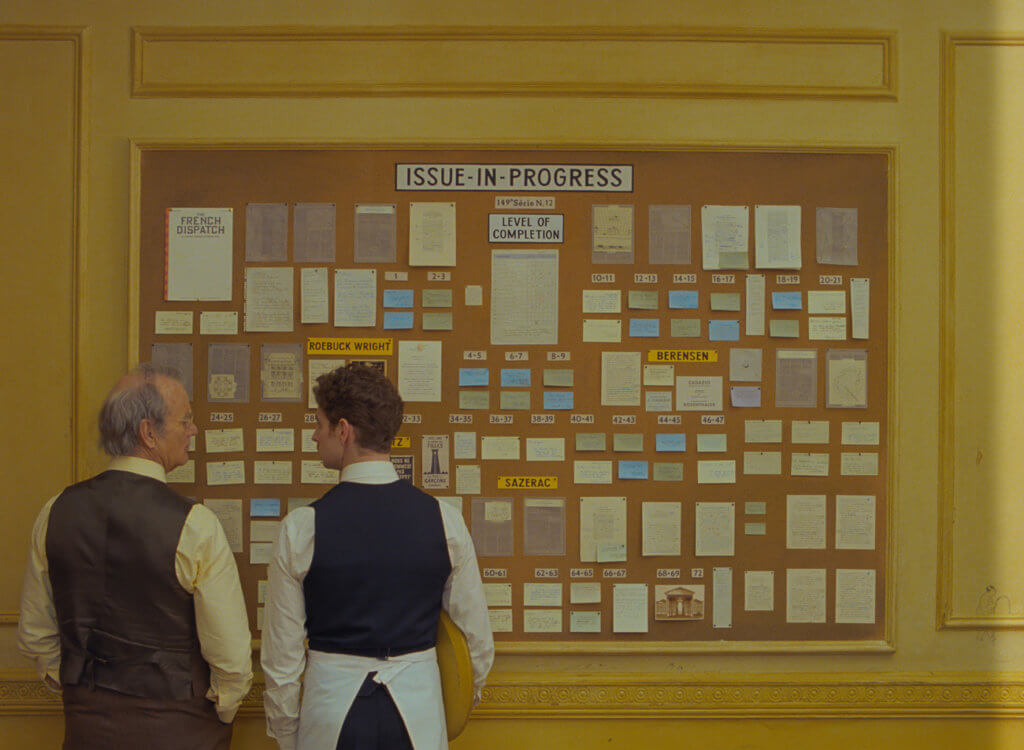

The editor’s role in an Anderson film begins long before shooting ends, but it also requires substantial work in post-production, including split-screen trickery to combine actors shot separately and other VFX elements. Weisblum discussed these with us, along with many other aspects of his work on The French Dispatch—a film containing three disparate yet related stories.

Filmsupply: Do you find maintaining your association with certain filmmakers over the course of several years one of the joys of the profession?

Andrew Weisblum: Yeah, I find working together frequently and sustaining ongoing relationships is a joy, because there’s an art to the collaboration. That, plus the work itself, makes things fun; additionally, the process becomes more streamlined due to the shorthand that develops in our communication.

With French, were there any particular challenges that set it apart from previous films?

There were new logistical aspects on this one that factored in, making this more complicated than our other live-action films.

We have stop-motion animation and physical miniatures, plus all sorts of different practical components relating to the stage work, but our working methodology was largely the same.

What kinds of visual references did Anderson provide?

Sometimes he’ll share with me an idea clearly referenced from another film or a photograph. Or, if we’re grappling to nail things down, I might bring a particular reference to the table. Because we do an animatic for the whole film, sometimes that becomes the reference. Even if it wasn’t intended that way, the animatic can be more than just a guide—it can become an inspiration.

He uses storyboards to figure out his frames: what those shots are going to say or do, how they function in the storytelling. And this becomes an efficiency tool, excellent for helping us to figure out what is going to be getting shot. A lot of times sets are built with only the elements we know will be in frame, just to keep the films economical.

Does that free things up when it comes to finding a location?

A lot of the sets and locations chosen would not be ideal if you shot a lot of typical coverage, having to shoot one way and then turn around. Since we know which directions we’ll look in advance and can be detailed and specific about that portion of things, the rest of the environment out of frame is irrelevant.

When I first read the script, I noticed that in the opening fifteen pages, each line seemed to represent a new set. From my past experience with him, I knew that didn’t literally mean a new environment each time. He has specific shots in mind to help him hit these beats. It’s a form of laser focus when shooting, and that extends to editorial.

How did the animatic process affect your end of the work?

Most of the film was done as an animatic. The film is a series of short stories, so we’d find ourselves essentially filming a new movie every few weeks, with new characters, actors and locations.

But things weren’t fully mapped out all the way through because animatics ran out of time. We were shooting the first story at a point when the last story’s animatic hadn’t been fully fleshed out or even finished.

With the number of well-known stars, do you still need to give their characters a solid introduction to the audience?

We don’t usually pay much attention to that aspect. It’s much more about how important their character is to the story and the telling of that story than their star wattage. Bill Murray’s character is pretty significant editorially, and he gets an introduction, while others are important, like Saoirse Ronan’s, they are presented according to story dictates.

What did require a lot of finessing and attention were those moments when we switched aspect ratios and went from black-and-white to color — and how we integrated characters from different shots via split-screen. There wasn’t always a set-in-stone plan with these events, so a great deal of work and imagination went into creating approaches and refining them until they worked for the story and felt stylistically appropriate.

Were there particular colorspace issues when it came to integrating the miniatures and stop-motion with the live-action?

That was all shot on film; even some of the still imagery used photographic elements, so even though there was quite a disparate collection of bits, it was just a question of getting things to fit together in the way we liked. We scanned the 35mm live-action in 4K as part of our dailies process. Everything I worked with on the Avid was a direct downrez of that scan, so any check work I did lined up pretty cleanly with the final files, meaning there’d be no mysteries in the DI.

Also, with the miniatures, a photo-real look was not often a goal. We’d be trying to attain some visual that Wes either had in his head or found a reference for. And sometimes there’d be a particular approach we figured out together. It wasn’t always about getting those disparate elements to fit together in some photo-realistic way indistinguishable from reality. That’s not to say there aren’t little effects applied invisibly and intentionally so. In terms of aesthetic tableaus for shots that include a lot of elements and require considerable tweaking, it was just a matter of getting them to work in a way that we liked.

So you take the position of arbiter during the DI?

I’m the gatekeeper on a lot of this. We worked with files that had CDLs taken from the master scan. After working things out early on with our DI colorist Gareth Spensley and grading certain still images based on the files, we’d often re-render dailies to get certain tweaks in there. It used to be when you cut on film, you’d have full-on color-grading and mixing later, so everything was a temp, including the sound effects.

Now we work with sound and sound effects that wind up in the final mix. There’s not a moment where you’re tossing a temp in favor of something that is expanded in some way – instead, we’re acclimating. Now we think about color-correction, visual effects, and contrast early on, instead of it all having to come together at the 11th hour in a single rushed DI pass. In a strange way, it is one of the last things for the digital workflow to have caught up on editorially, but it makes things so much more efficient.

Read more with 10 Award-Winning Editors Share Key Components of the Craft.