John Ruskin famously said, “Quality is never an accident.” That may be true, but how do you know quality when you see it? It seems to be a moving target. For example, John Krasinski’s YouTube sensation Some Good News may not fit into some filmmakers’ definitions of quality.

But, producer Josh Senior and his post-production team at Senior Post are thinking a little bit differently about production value these days. And the success of their work on the show seems to speak for itself.

“That’s the most exciting part of the whole thing, really. You don’t need everything you thought to make something that’s worth watching,” Josh told us. “It’s not about a camera. It’s certainly not about sound equipment. It’s the little things we’re doing that seem to make the difference.”

He credits much of the success of Some Good News to it’s lo-fi aesthetic, it’s off-the-cuff relatability. But still, the aesthetic was chosen strategically. Just because their show looks like it was cut by someone’s nephew, doesn’t mean it was. “Quality is never an accident,” and his team is putting a lot of expertise and thought behind it. And that’s what makes it work.

Globally, we’ve all heard these are “unprecedented times,” but the same is true for creative filmmaking. Workflows and perspectives are changing. Shows like Some Good News are giving new meaning to the value in production value. They’re connecting with millions of people around the world and bringing positivity into their homes.

We talked with Josh about how he and his post-production team are intentionally being unintentional with this project, how they’re finding new versions of success in strange times.

Filmsupply: How were you connected with John Krasinski on this project?

Josh Senior: The president of Communo and I actually used to work next door to each other. He reached out and said, “Hey, we’re having some trouble getting the tone right on this thing that John Krasinski’s making from his house. Can you see if Senior Post might be able to hop on it today and fix it? We want to go live tomorrow.”

He had already filmed a bit of it and there was an edit, but there was no “show” yet. They couldn’t find the right tone and weren’t sure if they were going to put it out or not.

I woke everybody on my team up at 8 a.m. on a Saturday. It was our second week working from home. We had just lost a ton of business and everyone was pretty down in the dumps. I said, “Hey, this is why we got into this. Let’s take a crack at it. We don’t know if it’s going to be a job. We don’t know what it’s going to be, but we’re well-suited to tell this type of story. Let’s go for it.”

It seems like it developed into a real job.

The first episode went really well. We realized this was an opportunity for us to do something that made people happy. It started to take off and the Zoom interview with Steve Carell went viral, which was really exciting. But it wasn’t a job yet. We hadn’t spoken to John at that point.

After the first episode, we all started to get to know each other and decided we were going to do it again, and make it into a real project. We started being a little bit more strategic about how we packaged assets, the run time, and the content.

Unlike some of the work we run through the post house, which is very much service-based, we were having conversations at this point. We were collaborating and coming up with the right way to tell the story but also what the story should be, so it was this perfect opportunity that everybody in post always dreams about—not just getting a hard drive but actually having a conversation about what, why, and how it’s going to be made. We actually have a production company inside of our post house called LEROI, and this show is the perfect manifestation of the two.

What was your process for honing in on an overall style and tone?

We always ask ourselves, “What is the most elegant version of this conversation that doesn’t tell you how to feel?” In editing, a lot of work is engineered to give somebody a reaction and with this show, we’re really trying not to do that. We’re trying to let these things play out and present them in a way that’s palatable, but also doesn’t have an objective. There’s no agenda. Creatively, we’re encouraging the team to not do a lot of the things we’ve learned over the years.

Is that difficult? It almost seems like you’re asking thoroughbred horses to trot.

That’s exactly what’s happening. For example, my business partner, Joanna Naugle, is the lead editor on Ramy on Hulu, she’s done tons of comedy specials and narratives and films, and she’s making a very deliberate choice to make it feel like someone’s nephew cut it. That’s the point. The best compliment we could get is that it feels like it’s homemade and there’s a lot of restraint going into that.

I hope that it doesn’t feel like a clip show. There’s a throughline and it’s put together in a holistic way. It starts with John, to be honest. I’d love to take all the credit for that, but it starts with him.

Does it make you think differently about the “value” in production value?

That’s the most exciting part of the whole thing, really. You don’t need everything you thought to make something that’s worth watching. There’s a lot of novelty in terms of the conversations we’re having about how we’re approaching the work and what can be made right now.

It’s not about a camera. It’s certainly not about sound equipment. It’s the little things we’re doing that seem to make the difference. We’ve seen people put together shows that resemble ours, and I think it’s great to see ours resonating without a lot of tweaks.

It seems to be more about collaboration than process.

Absolutely. This is one of the only things I’ve done with such a high profile talent that feels like I’m making something with my college buddies. That’s an important thing to note. There’s no bureaucracy to this. If I need to talk to anybody, they’re available to me. If I have an idea and opinion, I’m pitching it. If I think something’s wrong, I push back on a note.

John and I have never met in person. But, we all have this rapport and shorthand that really feels symbiotic and it resonates in the work. You see all of us having a great time making it and that’s bound to be part of the way people experience the show.

While it is lo-fi, it does seem incredibly cohesive. How do you nail that with all of the different formats?

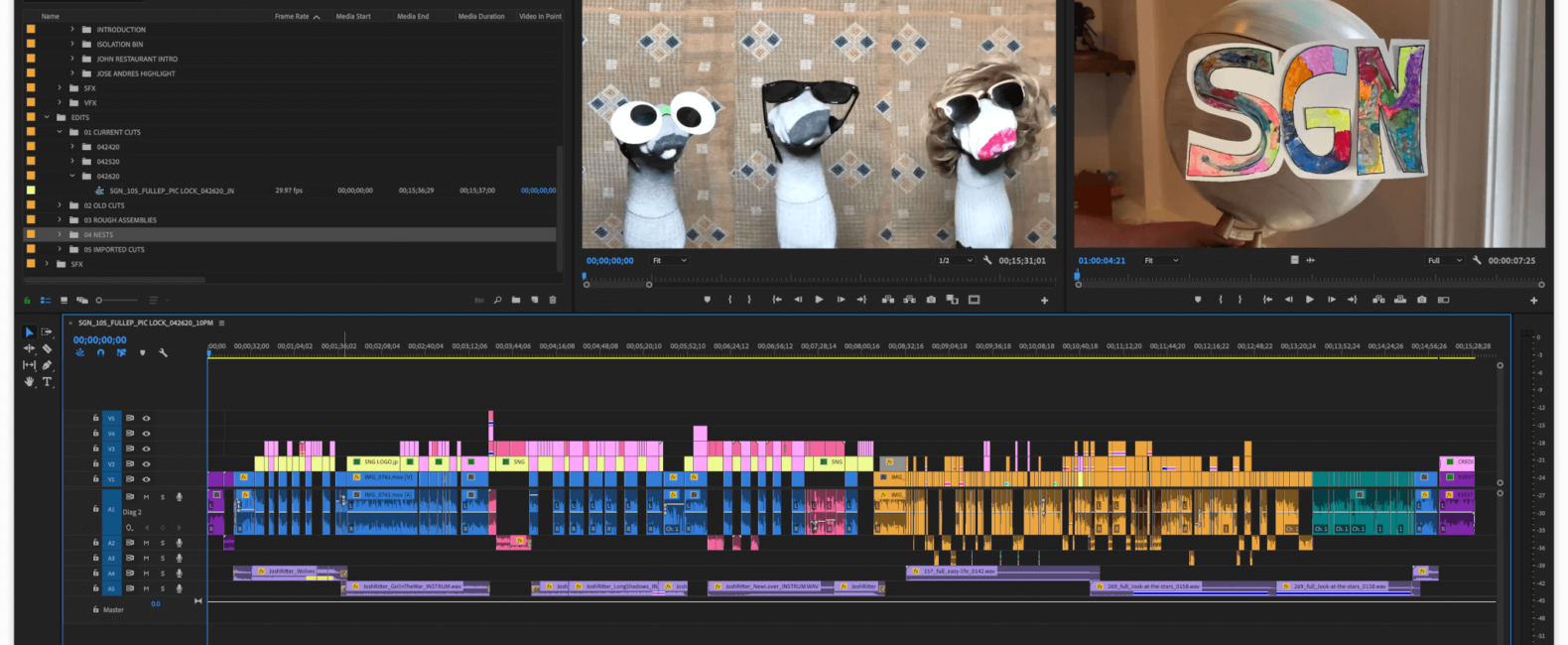

We work with most of the assets natively. We don’t do a lot of transcoding or post processing. All the files are pretty light, so whoever’s cutting, they all have mirrored assets. Our post-producer came up with a really great guide and everyone just mirrors their desktop or the folder on their computer that has the assets to match the same protocol.

We use Adobe Premiere, which is great because it takes all sorts of files without any sort of repackaging, transcoding, or rendering. We’re broadcasting on the internet, so the quality standards for media on some of the networks aren’t really an issue here.

We do some post processing on the assets in the online phase after it’s all edited just to make it all feel great. Sometimes mixed frame rate footage looks choppy and skippy. Sometimes there are dropped frames in people’s iPhone videos, motion blurring, or things like that, and we fix it. But, at the end of the day, I don’t want you to know that when you’re watching it.

The real guiding principle is how natural we can make it feel. We don’t want the team who’s cutting this to feel like they’re tapping into the matrix to make this video.

Other than fixing and not doing things, what are some of those proactive things you do in post?

You mean our secrets?

Yeah, if you could share those that’d be great.

[Laughs] Well, I can share a few.

Sound, to me, is such an important thing when it comes to determining quality. People have the latitude for a lot of variance in terms of video quality, but if the sound is all over the place, it really takes you out, so that’s something that we really focus on.

The other thing is cadence. Professional editors are really good at pacing. We’ll do things like rotoscoping distracting elements that don’t belong. We’ll make sure the transitions between John and the clips are natural and not punctuated in a way that creates some sort of impression. We’re really cognizant of the Kuleshov Effect. We want to make sure John’s face and the thing you see next isn’t implying something.

Our filmmakers are bringing a lot of film theory into the work, and it shows in an invisible way. Joanna has a series of video essays on No Film School about editing techniques and tactics, and those are the things she’s innately bringing to the work.

We spend a lot of time talking about where things happen in the show, too. Rather than focus on how paced-up or down a segment is, we take a high-level approach. How do we show things in a sequence that’s going to derive happiness? Solving for a positive outcome is a really novel way to make a film or a video, and it’s not something we’ve done before. If we can answer that question every time, we know it’s the right choice.

Will this project affect how you view your other work?

Absolutely. If you had asked me six months ago what Senior Post was, I would have said, “We’re a really big, young, exciting post house in Dumbo, Brooklyn, where you can make your film or television show in a beautiful environment with a lot of great people.” That’s not what I would tell you today. Today, I think we’re a team of problem solvers who bring the right approach to whatever the project calls for. We’re people with a point of view and the ability and ethic, work ethic, to get stuff done.

To me, the testament here is that my team has found a way to be productive in a really challenging time. The feeling I’m left with is an overwhelming sense of pride for the way that everyone who I work with sees their work. It’s important, but it’s fun. It’s special because it’s giving people a good feeling. We really enjoy making television shows, comedy specials, documentaries, features, and all that stuff is great. But, this is the first thing I’ve ever made that I’ve been able to show my kids. That really resonates.