It’s one thing to look back on a career and reflect on what you’ve learned. We’ve talked to plenty of filmmakers with that perspective—and it’s certainly valuable—but this conversation is a bit different. Editor Chris Tonick is smack dab in the middle of his career. Sure, he’s done work on acclaimed projects like Guardians of the Galaxy, John Wick: Chapter 2, Star Trek Into Darkness, and much more, but “making it” in the film industry is still fresh on his mind.

That’s why we wanted to speak with him. To pick his brain on what it took to find a big break in the film industry. Much like any great story, Chris’ started with a leap of faith:

I wanted to work in scripted features. It’s always been my first love. I made the decision to save up money for about a year and move out [to LA]. I could live here for six months and try to find something.

Since we’ve already spoiled the ending and mentioned that Chris found success, we’ll go ahead and drop another tease: the secret to how he got there. Chris was kind enough to share his thoughts on making the move to LA, networking, industry politics, and landing his first lead editor role.

Here’s editor Chris Tonick.

Filmsupply: What prompted your move to LA?

Chris Tonick: I was at a college football watching party with a friend of mine, and his dad was asking what I did for a living—“So, you edit things?” I said, “Yeah.” And he mentioned that a friend’s son did that too. I asked what he edited, and I was expecting the answer to be wedding videos, but he said, “He edits this show called Mad Men.”

They got me his email address, and he turned out to be an editor named Tom Wilson. I emailed him and told him that I was an editor in Dallas working on commercial stuff, but my heart has always been in narrative work. He gave me a reality check and said, “Nothing you’ve done in Dallas is going to count in LA. It’s not fair, but it’s the truth. You’re going to go look for a job, and if it’s not New York or LA, they’re not going to think it matters.”

(Image via Chris Tonick)

I thought long and hard about what I really wanted to do. And when it came down to it, I wanted to work in scripted features. It’s always been my first love. I made the decision to save up money for about a year and move out here. I could live here for six months and try to find something. It ended up paying off within about three months when I got a gig on a reality show. It wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to be doing, but I was making a living in LA and was able to pay my bills.

Scripted filmmaking still operates very much like a small town. Nearly every job I’ve gotten has been from a recommendation because those jobs don’t go up on the internet. It’s still pretty old school. They don’t want to be the first one to toss you the car keys. They’re going to rely on someone else saying that this person’s dependable and also someone you don’t mind being in a room with for 12 to 15 hours a day.

It’s funny you mention that. We’ve had so many editors mention “likability” as a key hiring attribute.

You can get those people who are amazing at their job but suffer from an excessive or unpleasant personality. They may be great, but you’re literally going to go crazy. The hours can get long. I try and keep it reined in, but there are definitely long hours in features. Especially if you’re working on something for Marvel or DC or one of these bigger places; they’re not worried about the overtime bills. I’ve worked 15- to 18-hour days for 20 days straight. It happens occasionally. So, when you’re in the trenches with somebody, being likable goes a long way.

There’s definitely a balance of likability and also having a backbone, right?

There’s always that line of balancing the politics of it. I’ve got to push back sometimes. I was talking with a friend earlier this year about how many times you should push back on a note. We landed on, “probably twice.” [Laughs] You push back once, get refused, and then you let it lie for a day or two. And then you push back one more time and sometimes it gets shot down again. At the end of the day, you’re essentially a mercenary, but you want to be a collaborator too. But, you’re right. You can’t be a pushover.

I remember being in school and people telling me, “You’re really going to have to do some networking.” I always thought it was going to be a super awkward experience where you give people your business card. But really, it’s just about finding the balance through social cues of having a personality and being someone who’s not going to bail when the going gets rough. In other words, networking was just hanging out and making friends.

When did you feel like you were breaking through?

My first job was actually from a guy I knew on Twitter. He’d gotten an assistant job on an indie film, and he was going to leave his job at a reality TV studio here in town. I ended up coming on and thought I was just getting hired for a show, but I ended up staying there for about a year and a half or two years. Eventually, that same guy went to work at Bad Robot as an Avid tech, and he told me they needed an in-house assistant editor.

He called me up and asked if I was interested. It would be a one-week test run, and he couldn’t guarantee anything beyond the week. I went there for a week and stayed for a year. I ended up working on Star Trek Into Darkness and making a lot of friends with the post crew there. It felt like the environment I wanted, like a movie summer camp. It was a really free-flowing, collaborative process. We’d grab the RED and shoot a clip on the post supervisor’s desk and it’d end up in the movie. It felt like being back in film school.

(Image via Chris Tonick)

From there, I ended up getting my first assistant editor gig on this Salma Hayek movie called Everly. I worked on Guardians of the Galaxy and John Wick: Chapter 2, which was a pretty phenomenal experience. And then getting to do Once Upon a Time…In Hollywood was incredible—I worshiped at the alter of Tarantino in film school.

Having left commercial work to go to narrative work, do you think doing multiple media is possible, or is that crossover difficult?

I think there’s a stigma between different formats. You even see it in streaming, where there are different departments for features and series, and different post executives run each. They do not tend to cross-pollinate their editors. It’s strange because you’re working in a world completely divorced from the necessity of run times. An episode can be as long as it needs to be. Why is someone who cut a 90-minute feature not equipped to cut a 75-minute episode of a streaming series? It’s just a different mindset.

(Image via Instagram)

Normally, it seems to come from the non-creative side. The only thing I can assume is that people are trying to minimize risk—they don’t want their decisions to somehow come back and bite them because this editor has never cut a TV show before. To me, storytelling is storytelling. There are different rhythms to a broadcast show versus a film, but more and more, the line between a film and a TV show is getting muddied.

Do you find yourself passing up jobs because of that siloing?

I definitely have. I’ve passed up VFX effects editing jobs because I knew it wasn’t something I wanted to pursue. I’ve done moonlighting gigs between movies, where I’ll come on for eight weeks as a VFX editor and not get credited. It’ll pay the bills, but I’m not necessarily seeking out this work. I know plenty of feature editors who will take a commercial gig in between their features, but it’s normally when they already have another feature already booked.

In general, the industry doesn’t do well with non-defined roles. They want to know you’re a wrench or you’re a hammer. Even if you tell them, “I can do both these things.” They’ll say, “No, no, no, no, you’re the hammer.” I feel it short-changes a lot of editors who would probably be willing to jump around. The only people I’ve seen who have the latitude to do that are your editors who have been nominated for awards for their scripted work.

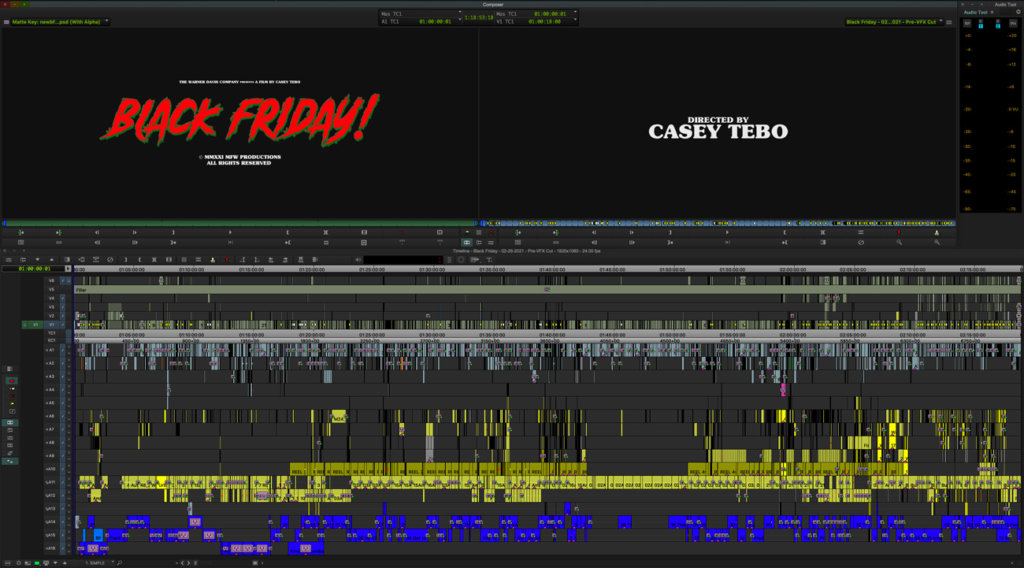

Black Friday was your first lead editor role, correct?

Yeah. It was a really fun movie to work on. The director knew a friend of mine and wanted to hire him to do the movie, but he was already on another job. He said, “You should talk to my friend, Chris.” I’m at that weird point where I’m trying to not take assistant work so I can take more cutting jobs.

I read the script, and I thought it was good. It’s a fun, John Carpenter-type of project, like an eighties throwback. They shot it in 15 days in Boston, and I stayed here in my office in the valley and got all the footage remotely. I didn’t see anybody else in the movie until we were in the mix. It was a very different way to cut a film. As somebody who grew up loving Bruce Campbell and Army of Darkness, when they told me he was playing the store manager, I said, “I’m in.”

Were you thinking about the film from a career-building perspective?

It definitely enters into some of the calculus. One thing that was appealing about Black Friday was that it was a horror film with names attached to it. It will likely sell, and people will see it. That’s definitely a danger when you’re working in the Indie space. You can make a beautiful, amazing film, but if nobody watches it, it’s going to be hard to get other work out of it.

(Image via Chris Tonick)

Another part of what I found appealing about the project was that it was something tangible I could point to when I reached out to agents—here’s the trailer, and it has several million views on YouTube. It’s been on the top of the iTunes charts for three weeks in Horror. I definitely felt it had a better chance of getting traction. I love a heartfelt, indie, coming-of-age story, but they don’t exactly get checked out much, even on VOD.

Looking back to your entry into the LA scene, what advice would you give to a filmmaker in that same position?

There are two things I’d say. First, none of your experience is wasted. There’s stuff I learned at my first job out of college that I’m using now. There were tech skills that I learned working on corporate and reality TV that came into play on giant features. We’d need to encode this file, but nobody knows what this format is. But, I knew the format because we had to deliver it to a cable network when I was working on a reality show. You never know what experience is going to influence or come into play in a positive way down the road.

The other piece of advice is that I tried to think about what I ultimately wanted to end up doing. Use that as a signpost, as far as if something was the right call or not. Neil Gaiman had a speech he gave to some graduates where he was talking about freelancing as this idea of walking toward a mountain. Your path to the mountain may go all these different directions, but as long as you’re generally headed toward the mountain, you’re moving in the right direction.

There may be a time where you say no to a job you previously would’ve said yes to because at the time it was moving you in the right direction. But now it’s not. What did I want to do? I wanted to work on narrative features, and I wanted to cut narrative features. With every job, I had to ask, “How does this move me towards that goal?” Even if it was a move that was five steps to the side and a half step forward, it was still a half step forward.

Ask yourself, “What do you want to do?” If you like fast-paced work and always working on something new, then maybe commercial work is the way to go. For me, my first love has always been long-form storytelling. So, as far as where I was going, it was never even a question.

Read more about film editing with The Gatekeeper: Editor Andrew Weisblum on ‘The French Dispatch‘.