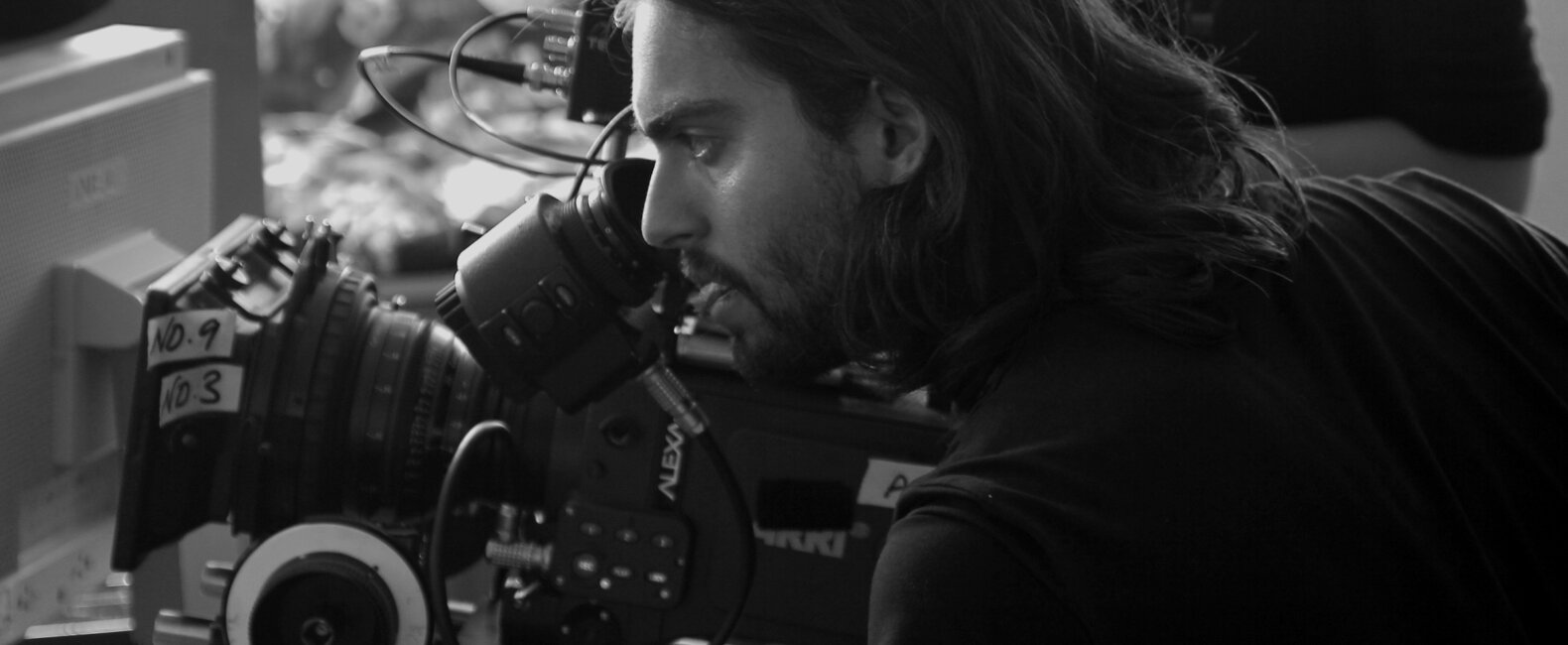

There are no rules in cinematography except the ones you set for yourself, and even those are made to be broken. At least that’s the way Paul Özgür operates. He’s an award-winning narrative/commercial/music video cinematographer who is quickly carving out a name for himself as one of the great up-and-coming filmmakers of our time.

Here are a few of his frames.

THE WOUND

This still is from the film The Wound, directed by John Trengove. It’s about a South African businessman who wants his son to experience the initiation rites of his old tribe. It takes place in a very secluded world, a very masculine world. The story also involves same-sex desire in a culture where homosexuality is a big taboo.

The reason why I chose this particular frame is because, for me, this shot defines how we were forced to rethink our entire approach to the shoot and learn to embrace what the film needed. When I get involved with a film, I always ask what the character’s motivation is—what are they feeling, or what’s going through their minds? This helps me develop certain cinematic rules to the shoot, so we can motivate our approach to each scene. I try to find a cinematic language that puts the director and me on the same page. This helps ensure that I don’t get lost during production, when so many things can distract you.

On The Wound, however, my usual approach wasn’t working. Many of the characters were played by nonactors, and they contributed so much of their own personal experience to the story that we were forced to respond. We started with a very visual concept of how we were going to capture the world these guys live in; but then, once we were immersed in their world, we realized how much we didn’t know. Obviously, the director had done his research — nearly six years’ worth — but the actors would tell us, “Oh, we wouldn’t do it this way. We’d do it that way.” When we looked at the rushes after the first two days of shooting, we realized our entire strategy for the shoot was wrong. We were way too dominant. We weren’t respecting what was in front of us. We needed to start over. And it turned out to be the best decision we made for the film.

We immediately went to a more open and free form shoot, establishing a 360-degree environment on the set. I typically try to do that anyway, but in this case it was essential. We wanted to play scenes from start to finish without pickups. Some shots would be 5 minutes long and some would be 20. It was extremely tough for the crew because we were shooting in the summer heat, and everything was hand-held. Everybody had to be on top of their game. But it was such a liberating way to shoot.

So back to this particular frame and why it’s so important. It’s from the movie’s big breakup scene when the two main characters get in a fight and end their relationship. For weeks, I’d struggled with how I was going to shoot it. It was a seven-page scene, and I was worried because it was very scripted. It was missing something, but I didn’t quite know what it was. I found it almost by accident.

While we were doing pre-production, which was for three months, I’d walk around a location and take pictures of the landscape to get inspiration. One evening, I was walking on this hill when the sun went down. Because it was winter, I was completely overwhelmed by the speed of the sunset. It literally went down within seven or eight minutes, and you could see it popping behind the mountain. That, for me, was the moment. That sunset would symbolize the relationship between these two men coming to an end. The warmth of the sunlight turning into a very cold, blue night felt like the closing of a chapter in his life.

Obviously, proposing something like this to a director means you have to explain that you get only one shot at the scene per day. Plus, you have to have a strategy for making it work. I had to execute my idea without overshadowing the performances just because I want to capture a nice sunset. It had to serve the story. This is the shot that reminds me you have to put away your ego and respect what’s happening right in front of you.

Nuts & Bolts

This particular still was shot with a 75 mm anamorphic lens. We basically shot 95% of the film on a 75mm, and a little bit on a 50mm. They’re very limited, but that’s a good thing. It’s so cliché, but less is more. Give yourself restrictions.

PRINCE

I love beautiful shots that contain beautiful imagery; but if the image becomes too dominant or too overwhelming, then you’re in the wrong place. I think the hardest challenge as a DP is to tell the whole story in a single frame.

This is a still from my first proper feature, Prince. It was an extremely low-budget film and probably one of the hardest jobs I’ve ever done. Not physically, but mentally. We were working with nonactors, and they were all teenagers. They were very tough to work with. The director, Sam de Jong, had a background in documentaries, and he met this kid Ayoub, the main character, while he was doing a film about street kids. Ayoub had a certain energy about him. Sam pretty much wrote the film around him and for him. Ayoub’s done one film in his life — this is the only film — and he completely nailed it.

So why did I choose this frame? As I mentioned with The Wound, I always try to establish these rules: why I choose a set of lenses, why I choose a certain way to light. Do I backlight it? Do I use a single source? Do I use multiple sources? In this case we had a very strong visual concept for the film. The first thing Sam said to me was, “Dude, I want this to be a 90-minute music video.” I was like, “Cool. We’re going to apply music video rules, and then we’re going to break them.”

We focused on singles. We were always dead-on on the kid. There was no movement. We’d move only when the actor was moving. This way, the audience would identify with the character throughout the film; because as he’s going on his emotional journey, the camera is right there with him. I decided to literally measure the eye height of the main character and start there. For other characters, I would be lower and more at an angle; and I’d use different distances and change the eye line. That was the overall strategy. But there was this moment in the film when I felt like we should break all the rules. As the film moves toward its climax, the kid becomes the king of the street, a prince. He gets hooked up with the wrong guy who takes him on this trip in his purple Lamborghini. He does drugs for the first time, and he literally feels like he’s a boss. I thought, How cool would it be to give this moment a Polaroid feel: use a flashlight on the main camera, shoot it on high speed, and have him look right at us? It could be such an incredible moment when he gets the crown, starts to close the car door, and keeps looking in the lens.

It was the last shot of the day, and I told Sam, “I need to do this.” He said, “Go for it.” I had my gaffer put a light above the camera, flash it in, and turn off all the lights. Then I told the actor to look straight into the camera. I wanted it to be the kind of shot that when people think about Prince, they think of this image. Afterward, I was convinced it wouldn’t make it into the film. I thought it was too weird or experimental or whatever. But they actually used it! And for me, this frame not only sums up the film, but it sums up what cinematography can be.

Nuts & Bolts

We shot the entire film on one lens — a 25mm Super Speed on a 2.8 stop.

THE FORMULA

This frame is from a music video. I love doing music videos. Nowadays, they’re more like short films — like art pieces. They have that beautiful balance between commercial and cinematic storytelling. This was a special project for me because Emmanuel Adjei — an amazing director — directed it, and my sister, Marleen Özgür, wrote it. It’s about a woman who had a miscarriage and can’t deal with the loss of her baby. She ends up taking her own life.

Emmanuel made me feel like I was co-directing the film. I know a lot of cinematographers want to become a director, but I don’t think I ever will. So I’m not a director at all, but I felt like Emmanuel had respect for my vision. Sometimes he didn’t even look at the monitor. Obviously, that’s a huge compliment. He knew whatever I was capturing would be similar to his taste. It’s always great to find a collaborator who’s on the same page as you.

Music is an important inspiration for my work. When I’m working on a narrative, whether it’s short or long form, I try to find appropriate music to listen to during pre-production. Even better is when a director shares their music with me before we start production, because then I know the mood of the piece and what they’re heading toward. Sometimes on set, when I’m operating a shot, I hear music in my head that I think fits it. It probably sounds pretentious, but in that moment I like to imagine the music the scene should be cut with.

We shot this music video in Poland. We had almost no money, but we managed to find this incredible house. The owner didn’t build it on the right foundation, so it was literally falling apart. It had cracks everywhere. There were two main parts to the house: the back and the front. The front was always very bright with big windows. The back of the house was very dark, which I thought of as the character’s cave, her inner self.

We shot this in a 360-degree environment. I wanted to let the actors play and do long takes. I prepped all the rooms with the right amount of lighting. And we had this room that felt like a set, but it wasn’t a set. It had the perfect energy, and it got everyone — from the designer to the actors to me — in the right mood. I decided that for the pivotal scene, I would flip things around so the back of the house was very bright. I overexposed it and put it on a higher ASA. I think it was shot on 1600. This was a moment of enlightenment, and I wanted the whites to be whiter than white. It was carefully planned.

I chose this particular frame because the white insect she’s holding wasn’t planned. It literally flew into the room while we were shooting, and she just took it and looked at it. It completely matched this carefully selected white environment we’d chosen. This frame kind of combines the reasons why I picked the other two frames as well.

Nuts & Bolts

This was shot on an Alexa with a Steadicam. The lenses were Master Prime. I think it was a 21mm. I love using those lenses. They’re very fast, very big, and very lightweight.